The Fundamentals of Building Projects: We’ve all been there. A flash of inspiration strikes in the shower, on a late-night walk, or in the middle of a mundane task. It’s a brilliant idea for a project—a mobile app, a handcrafted piece of furniture, a novel, a community garden, a new business venture. The initial excitement is a potent, intoxicating force. You can see the finished product in your mind’s eye, perfect and gleaming.

But then, reality sets in. The path from that brilliant spark to a finished, tangible reality is often a fog-filled, treacherous landscape. Many projects die in this fog, becoming ghosts that haunt our to-do lists and our sense of accomplishment. They become the half-built bookshelf in the garage, the abandoned code repository, the first three chapters of a novel that never went further.

The difference between those who consistently bring their ideas to life and those whose projects languish is rarely a matter of talent or intelligence. More often, it’s a matter of process. Successful builders, whether they work with code, wood, words, or people, rely on a fundamental framework. They have a map for navigating the fog.

This guide is that map.

Over the next 5,000 words, we will deconstruct the entire lifecycle of a project, from the first glimmer of an idea to the final moment of completion and reflection. This is not a rigid, one-size-fits-all formula, but a universal, step-by-step approach that you can adapt to any project you can imagine. We will break it down into five distinct, comprehensive phases:

- Phase 1: The Genesis – From Spark to Scope. Turning a vague idea into a defined, achievable goal.

- Phase 2: The Blueprint – Charting the Course. Creating a detailed plan of action, anticipating roadblocks, and gathering resources.

- Phase 3: The Forge – Bringing the Blueprint to Life. The core execution phase where the work gets done, momentum is built, and challenges are overcome.

- Phase 4: The Crucible – Forging Quality Through Refinement. Testing, gathering feedback, and iterating to transform a functional product into a great one.

- Phase 5: The Summit – Reaching the Finish Line and Looking Back. Completing the project, launching it, and conducting a post-mortem to learn for the future.

To make these principles tangible, we’ll follow two hypothetical projects throughout this guide:

- A Digital Project: Sarah, a web developer, wants to build a custom, minimalist blogging platform for her personal use.

- A Physical Project: Ben, a hobbyist woodworker, wants to build a sturdy, custom garden shed in his backyard.

Whether you’re building an app or a shed, the underlying principles of success are the same. Let’s begin the journey.

Phase 1: The Genesis – From Spark to Scope

Every project begins with an idea, but an idea alone is not a project. It’s a seed. To grow, it needs fertile ground, water, and sunlight. Phase 1 is about providing those elements. It’s the process of taking a formless spark of inspiration and forging it into a clear, well-defined scope with a powerful purpose.

Step 1: Interrogate Your Idea with “Why?”

Before you think about the “what” or the “how,” you must relentlessly interrogate the “why.” This is the bedrock of your entire project. Your “why” is your North Star; it will guide you when you get lost in the weeds and motivate you when the initial excitement fades.

Simon Sinek famously advised to “Start with Why.” This is not just a business platitude; it’s a fundamental project survival tool. Ask yourself:

- Why does this project need to exist? What problem does it solve? What need does it fulfill?

- Why am I the person to build it? What is my personal connection to this problem? What skills or passion do I bring?

- Why is now the right time? Is there an urgency or an opportunity that makes this project relevant today?

For our examples:

- Sarah (Blog Platform): Her “why” isn’t just “to have a blog.” It’s deeper. Why? Because existing platforms like WordPress or Medium feel bloated with features she never uses, and their design constraints stifle her minimalist aesthetic. Why does that matter? Because she believes a clean, distraction-free writing environment will help her write more consistently and clearly. Her project’s purpose is to create a sanctuary for her own writing.

- Ben (Garden Shed): His “why” isn’t just “to store tools.” Why? Because his garage is a chaotic mess, and he wastes time searching for tools, which kills his creative momentum for woodworking projects. Why is a custom shed the solution? Because pre-fabricated sheds don’t have the specific layout he needs for his tools and workflow, nor the build quality he desires. His project’s purpose is to create an organized, efficient workspace that enables his primary hobby.

Your “why” provides intrinsic motivation. “Building a shed” is a task. “Creating a personal oasis of order and creativity” is a mission.

Step 2: Define the Problem and the User

With a strong “why,” you can now clearly define the problem you are solving and for whom. A common failure point is building a solution for a poorly understood problem.

The Problem Statement: Write a single, clear sentence that defines the problem.

- Sarah: “Writers who value minimalism lack a simple, elegant, and completely distraction-free platform to publish their work.”

- Ben: “Hobbyist woodworkers with a specific set of tools lack an affordable, durable, and custom-organized storage solution.”

The User: Who are you building this for? Even if it’s just for you, be specific. Create a “user persona.”

- Sarah’s User (Herself): A web-savvy writer who values aesthetics and simplicity above all else. Is frustrated by visual clutter and unnecessary features. Wants to control every aspect of her online presence.

- Ben’s User (Himself): A dedicated hobbyist with a growing collection of large and small tools. Values efficiency and organization. Wants a solution that is “buy it for life” quality, not a temporary fix.

Defining the user prevents you from building a generic product that serves no one well. Every decision you make later should be checked against the question: “Does this serve the user and solve their core problem?”

Step 3: Brainstorm, then Brutally Cull

Now, let your imagination run wild. This is the time for “what if?” and “wouldn’t it be cool if?” Grab a whiteboard, a notebook, or a brainstorming app and list every possible feature, idea, and flourish that comes to mind. Don’t filter yourself.

- Sarah: Dark mode, SEO optimization, social media integration, a complex tagging system, analytics dashboard, a paid subscription model, different themes…

- Ben: Skylights, a workbench, electrical wiring, a loft for wood storage, a rain barrel collection system, custom-built tool hangers, a ramp for the lawnmower…

This list is exciting, but it’s also a trap. This is the birthplace of scope creep, the silent killer of projects. You cannot build everything at once.

The next, and most crucial, step is to define your Minimum Viable Project (MVP). The term comes from the startup world (Minimum Viable Product), but the principle is universal. An MVP is the absolute simplest version of the project that still solves the core problem defined in Step 2.

Go through your brainstormed list and ask a ruthless question for every single item: “Can my project succeed in its core mission without this?”

- Sarah’s MVP:

- Can she create a sanctuary for her writing without social media integration? Yes.

- Without a way to write and publish a post? No.

- Without a complex analytics dashboard? Yes.

- Without a clean, readable homepage listing the posts? No.

- Her MVP: A system where she can log in, write a new post using a simple editor, publish it, and have it appear on a chronologically ordered homepage. That’s it. It solves her core problem.

- Ben’s MVP:

- Can he create an organized tool space without electrical wiring? Yes, for now.

- Without a floor, walls, and a waterproof roof? No.

- Without custom-built hangers? Yes, he can use simple pegs initially.

- Without a loft? Yes.

- His MVP: A structurally sound, weatherproof box with a lockable door and a solid floor. It solves the core problem of secure, dry storage.

Step 4: Create the “Not-To-Do” List

The MVP defines what you will do. Just as important is a list of what you will not do (for now). This is your primary defense against scope creep. Write it down and place it somewhere visible.

- Sarah’s “Not-To-Do” List (v1.0):

- NO user comments

- NO multiple authors

- NO themes or visual customization (beyond the initial design)

- NO analytics

- Ben’s “Not-To-Do” List (Phase 1 Build):

- NO electricity or wiring

- NO built-in workbench

- NO skylights or windows

- NO painting or exterior finishing (just weatherproofing)

This list isn’t about abandoning good ideas; it’s about sequencing. These are all potential “Version 2.0” features. By defining them as “not now,” you give yourself permission to focus and, most importantly, to finish.

At the end of Phase 1, you should have transformed a fuzzy idea into a sharp, focused mission. You have a “why,” a defined problem, a specific user, and a tightly scoped MVP. Now, you’re ready to build the map.

Phase 2: The Blueprint – Charting the Course

If Phase 1 was about defining the destination, Phase 2 is about drawing the map, packing your bags, and checking the weather. This is the planning stage, and its thoroughness is directly proportional to the smoothness of your journey. Many people who love the “idea” phase skip the “planning” phase, eager to just start doing. This is almost always a mistake. A few hours of planning can save you weeks of rework and frustration.

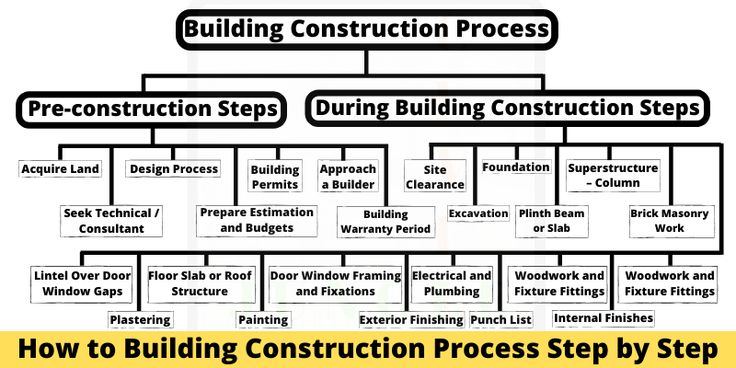

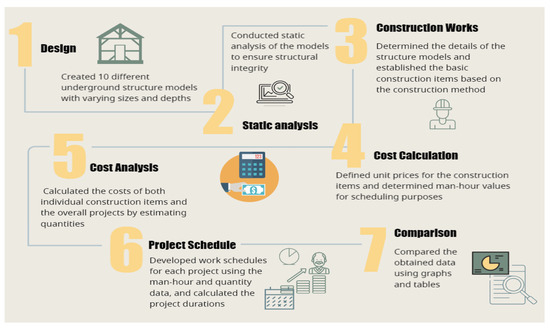

Step 1: Deconstruct the Project (Work Breakdown Structure)

You can’t “build a shed.” It’s too big and amorphous a task. It invites procrastination. You must break the project down into smaller, more concrete components, and then break those components down into specific, actionable tasks. This is called a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS).

Think in terms of large “epics” or milestones, then the “stories” or features within them, and finally the individual “tasks.”

- Ben (Garden Shed):

- Epic 1: Foundation

- Task: Clear and level the ground.

- Task: Build the frame for the concrete forms.

- Task: Mix and pour the concrete slab.

- Task: Allow concrete to cure.

- Epic 2: Framing

- Task: Build the floor frame.

- Task: Build the four wall frames.

- Task: Build the roof trusses.

- Epic 3: Assembly

- Task: Attach floor frame to foundation.

- Task: Install subflooring.

- Task: Erect the wall frames and brace them.

- Task: Install the roof trusses.

- Epic 4: Enclosure

- Task: Install exterior sheathing on walls.

- Task: Install roofing sheathing.

- Task: Apply tar paper and shingles.

- Task: Install the door.

- Epic 1: Foundation

Notice how “build a shed” has become a checklist of non-intimidating, clear actions. The same applies to digital projects.

- Sarah (Blog Platform):

- Epic 1: Core Backend Setup

- Task: Set up the database schema (users, posts).

- Task: Create API endpoint for user login.

- Task: Create API endpoints for Creating, Reading, Updating, Deleting posts (CRUD).

- Task: Implement user authentication middleware.

- Epic 2: Frontend Foundation

- Task: Set up the frontend framework (e.g., React, Vue).

- Task: Create the main page layout component.

- Task: Create the post display component.

- Task: Set up routing for home page and single post pages.

- Epic 3: Post Management

- Task: Build the login page.

- Task: Build the “New Post” editor page.

- Task: Connect the editor to the “Create Post” API.

- Epic 4: Public-Facing View

- Task: Fetch and display all posts on the homepage.

- Task: Fetch and display a single post when a user clicks on it.

- Epic 1: Core Backend Setup

This level of granularity turns an overwhelming mountain into a series of small, climbable hills.

Step 2: Estimate Time and Resources (The Educated Guess)

Now that you have your task list, you need to estimate how long each task will take. This is notoriously difficult. We are all victims of the Planning Fallacy, a cognitive bias that makes us consistently underestimate the time needed to complete a task.

So, how do you make better estimates?

- Be Pessimistic: Take your initial gut-feeling estimate and multiply it by 1.5 or even 2. This isn’t cynical; it’s realistic. It accounts for unknown unknowns—the problems you haven’t anticipated yet.

- Use Time-Boxing: Instead of saying “Task X will take 4 hours,” say “I will spend a maximum of 4 hours on Task X this week.” This focuses on allocated effort rather than predicted duration.

- Think in Blocks: Don’t use minutes. Use broad blocks like “half a day,” “one day,” “a few days.” This acknowledges the inherent imprecision.

Next, list the resources you need. This includes:

- Materials: Lumber, screws, concrete (Ben).

- Tools: Saws, drills, levels (Ben); A code editor, a database, hosting service (Sarah).

- Knowledge: “I need to watch a tutorial on how to properly flash a roof.” “I need to read the documentation for this authentication library.” Schedule time for this learning!

- Cost: Create a rough budget. What will you need to buy? This can be a reality check that forces you to re-scope your project.

Step 3: Sequence the Tasks and Identify Dependencies

Your tasks can’t be done in any random order. You must identify the dependencies. You can’t put up walls before the foundation is laid. You can’t build a “New Post” form that talks to an API that doesn’t exist yet.

Go through your task list and note these dependencies. This will naturally create a logical sequence of work. For more complex projects, this is where tools like Gantt charts become useful, as they visualize these dependencies over a timeline. For simpler projects, a numbered list is often sufficient.

- Ben’s Dependency: Wall framing depends on the floor frame being complete. The roof depends on the walls being erect.

- Sarah’s Dependency: The frontend login page depends on the backend login API being functional.

Step 4: Conduct a “Pre-Mortem”

This is one of the most powerful planning exercises you can do. It’s the opposite of a post-mortem.

Imagine it’s six months from now, and your project has failed spectacularly. It’s a complete disaster. Now, write down all the reasons why it failed.

This exercise bypasses our optimistic biases and forces us to confront potential risks head-on.

- Sarah’s Pre-Mortem: “The project failed because…

- …I got completely stuck on the authentication system and gave up.

- …I kept redesigning the UI over and over, never actually writing the backend logic (analysis paralysis).

- …I lost motivation because it was more work than I thought, and my existing blog was ‘good enough.'”

- Ben’s Pre-Mortem: “The project failed because…

- …I mis-measured the foundation, and the whole structure is crooked.

- …A week of unexpected heavy rain ruined my lumber because I didn’t have it covered.

- …The cost of wood was 50% higher than I budgeted, and I couldn’t afford to finish it.

- …I injured myself using the power saw because I was rushing.”

Once you have this list of failure points, you can create a risk mitigation plan.

- Sarah’s Mitigation: “I’ll use a well-documented, third-party authentication library instead of writing my own. I’ll time-box my UI design work to a single weekend. I’ll remind myself of my ‘why’ weekly.”

- Ben’s Mitigation: “I will ‘measure twice, cut once’ for every single piece. I’ll buy a tarp for the lumber before it’s delivered. I’ll get current quotes for all materials before starting. I’ll review power tool safety videos and never work when I’m tired.”

The Blueprint phase is complete. You now have a clear breakdown of the work, a realistic timeline, a list of required resources, and a plan for dealing with risks. The fog has lifted. You have a clear path forward.

Phase 3: The Forge – Bringing the Blueprint to Life

This is where the rubber meets the road. Phase 3 is about the sustained effort of execution. It’s often the longest and most challenging phase, a marathon of focused work. The excitement of the idea has faded, and the satisfaction of completion is still far off. Success in this phase is a matter of psychology, discipline, and momentum.

Step 1: Prepare Your Workspace

Before you make the first cut or write the first line of code, prepare your environment. A clean, organized workspace reduces friction and invites you to start work.

- For Ben: This is literal. Clean the area in the yard. Lay out the tools he’ll need for the foundation. Charge the drill batteries. Create a safe, clear area to work.

- For Sarah: This is digital. Create a new project folder. Initialize a Git repository. Install the necessary software dependencies. Set up her code editor with the linters and formatters she likes. Create a clean digital slate.

This act of preparation is a powerful ritual that signals to your brain: “It’s time to build.”

Step 2: Overcome the Inertia of the First Step

The blank page, the empty plot of land, the new project directory—they can be intimidating. The single most important thing you can do now is to start small.

Look at your Work Breakdown Structure from Phase 2. Find the absolute smallest, easiest, most trivial task you can do. Do that first.

- Ben: His first task shouldn’t be “pour foundation.” It should be “drive the first stake into the ground to mark a corner.” That’s it. It’s a 30-second task, but it breaks the inertia. The project is no longer an idea; it has begun.

- Sarah: Her first task shouldn’t be “build auth system.” It should be npx create-react-app my-blog or setting up the initial “Hello World” server. This creates the file structure and proves the environment works.

Completing this first tiny task provides a small dopamine hit and creates momentum. The next task then seems a little bit easier.

Step 3: Track Your Progress Visibly

Motivation during a long project is a finite resource. You must actively replenish it. The best way to do this is by making your progress visible. This creates a powerful feedback loop.

The simplest and most effective tool for this is a Kanban board. You can use a physical whiteboard with sticky notes or a digital tool like Trello, Asana, or Notion. Create three columns:

- To Do: All the tasks from your WBS go here.

- In Progress: Move a task here when you start working on it. Limit this to 1-2 tasks at a time to encourage focus.

- Done: When a task is complete, move it here.

The act of physically moving a card from “In Progress” to “Done” is incredibly satisfying. Over time, watching the “Done” column grow is a visual testament to your hard work, proving to yourself that you are making real progress, even on days when it doesn’t feel like it.

Step 4: Embrace the “Messy Middle” with Consistency

The “messy middle” is where projects go to die. It’s the long stretch of work after the initial fun and before the final push. The key to surviving it is consistency over intensity.

It’s better to work for one focused hour every day than to work for 10 hours one Saturday and then burn out for three weeks. This is Jerry Seinfeld’s “Don’t Break the Chain” method. Get a calendar. For every day you work on your project, put a big red ‘X’ over that day. Your only job is to not break the chain.

This builds a habit. It keeps the project top-of-mind. Even a small amount of progress prevents the project from going “cold,” which would require a huge amount of activation energy to restart.

Step 5: Navigate Roadblocks and “Bugs”

You will get stuck. Things will go wrong. Your plan from Phase 2 was a great guide, but it was not a prophecy. The map is not the territory.

- Ben might discover a large tree root right where his foundation needs to go.

- Sarah might find that the library she chose for her API has a critical bug or poor documentation.

This is not a sign of failure. It is a normal, expected part of the building process. The key is how you react.

- Don’t Panic: Frustration is the enemy of clear thinking. When you hit a wall, step away. Go for a walk. Sleep on it. Your subconscious mind is a powerful problem-solver.

- Isolate the Problem: Break the problem down. What, exactly, is not working? For Ben, it’s not “the foundation is ruined”; it’s “there is an obstruction at the northeast corner.” For Sarah, it’s not “the API is broken”; it’s “the POST request to /posts is returning a 500 error.”

- Consult an Oracle: You are not the first person to face this problem. Search Google, Stack Overflow, YouTube tutorials. Ask for help in a relevant online community or from a knowledgeable friend. Describe your problem clearly (what you tried, what you expected, what actually happened).

- Pivot or Persevere: Sometimes, you just need to push through. Other times, the roadblock is a sign that your initial plan was flawed. Be willing to change your approach. Maybe Ben needs to slightly reposition the shed. Maybe Sarah needs to switch to a different API framework. This isn’t failure; it’s agile adaptation.

The Forge is a test of resilience. By focusing on small, consistent wins, tracking your progress, and approaching problems methodically, you can navigate the messy middle and emerge with the core of your project built.

Phase 4: The Crucible – Forging Quality Through Refinement

You’ve built it. The shed stands. The blog platform functions. It’s a moment of triumph. But you are not done. You have a functional object, but you do not yet have a quality one. Phase 4 is about transforming your raw output into a polished, reliable, and user-friendly final product. It requires a difficult mental shift: from creator to critic.

Step 1: Systematic Testing and Quality Assurance (QA)

Now you must try, with all your might, to break what you have just built. This isn’t about just “checking if it works.” It’s a systematic hunt for flaws.

Create a formal test plan. Think of all the ways a user (or nature) could interact with your project, including the “wrong” ways.

- Ben (Shed QA):

- Water Test: Take a hose and spray the roof and walls from all angles for 10 minutes. Check the inside for any leaks.

- Load Test: Can the floor support the weight of his heaviest tools? Can the shelves hold what they are designed for?

- Usability Test: Does the door open and close smoothly without sticking? Is there enough clearance to move the lawnmower in and out?

- “Idiot” Test: What happens if he leans a heavy ladder against the wall? What if he slams the door?

- Sarah (Blog Platform QA):

- Happy Path: Can she successfully log in, create a post, publish it, edit it, and delete it?

- Edge Cases: What happens if she tries to publish a post with no title? With a massive image? With HTML code in the body?

- Error Handling: What happens if the database connection fails? Does the user see a friendly error message or a terrifying block of code?

- Cross-Browser Testing: Does it look and work the same on Chrome, Firefox, and Safari? What about on a mobile phone?

Document every bug you find in a simple list. No matter how small or trivial, write it down. Then, work through the list and fix them one by one. This is the difference between an amateur and a professional.

Step 2: The Art of Seeking and Receiving Feedback

Testing your own work is essential, but you are blinded by your own knowledge of how it’s supposed to work. You need fresh eyes. Seeking feedback is terrifying because it makes you vulnerable, but it is one of the most valuable things you can do.

How to Ask for Feedback:

- Be Specific: Don’t just ask, “What do you think?” Ask targeted questions. “Could you try to publish a post and tell me if anything was confusing?” “Could you look at this shed and tell me where you see the most obvious imperfections?”

- Prime Them for Criticism: Frame the request in a way that gives them permission to be critical. Say, “I’m trying to find all the flaws, so please be as picky as possible. You won’t hurt my feelings.”

- Choose the Right People: For early feedback, ask people you trust who fit your “user persona.” A fellow writer for Sarah’s blog; another DIY-er for Ben’s shed.

How to Receive Feedback:

- Shut Up and Listen: Your first instinct will be to defend your choices (“I did it that way because…”). Resist this urge. Just listen and take notes. You are not there to argue; you are there to collect data.

- Separate the Signal from the Noise: Not all feedback is created equal. You must learn to categorize it:

- Usability Problems/Bugs: A user couldn’t figure out how to do something, or something broke. This is gold. Fix it.

- Feature Requests: “It would be cool if it did X.” This is valuable but should be added to your “Version 2.0” list, not acted on immediately. Refer back to your MVP.

- Personal Opinion/Aesthetics: “I don’t like the color blue.” This is subjective. If you hear it from multiple people, it might be a signal. If it’s just one person, you can probably ignore it if it contradicts your own vision.

- Say Thank You: The person giving you feedback has given you a gift. Thank them for their time and honesty.

Step 3: Iterate, Iterate, Iterate

Now you have a list of bugs from your own testing and a list of feedback points from others. This begins the refinement loop:

Fix -> Test -> Get More Feedback -> Repeat

This is where the project truly gains its quality. Ben might add extra sealant to a leaky corner, sand a rough edge, and adjust the door hinges. Sarah might add better error messages, fix a layout bug on mobile, and make the “Publish” button more prominent.

Each loop makes the project incrementally better. Know when to stop—you can’t achieve perfection. Your goal is to eliminate all the major flaws and usability issues identified for your MVP. Refer back to your “Done” criteria from Phase 1.

Step 4: Don’t Forget Documentation

Documentation is the act of kindness to your future self and to your users.

- For Users: How does it work? Sarah should write a simple README.md file explaining how to set up and use her blog platform. Ben might jot down notes on the type of paint he used for future touch-ups or create a maintenance schedule.

- For Your Future Self: Why did I build it this way? Sarah should add comments to her code explaining complex logic. Ben might take photos of the in-wall framing before he covers it with sheathing, so he knows where it’s safe to drill later.

This step feels like a chore, but you will be immensely grateful for it six months or a year from now when you have to fix or update something.

Phase 5: The Summit – Reaching the Finish Line and Looking Back

You’ve built it, and you’ve refined it. The project is now solid. Phase 5 is about formally completing the work, releasing it into the world, and, most importantly, learning the lessons it has to teach you.

Step 1: Know When to Call it “Done”

The temptation to add “just one more thing” is powerful. This is the final stand against scope creep. Go back to the MVP you defined in Phase 1. Does the project meet every requirement you set out for your initial version? Yes? Then it is done.

It’s not perfect. It doesn’t have all the features you dreamed of. That’s okay. Shipping a “done” project is infinitely more valuable than having a “perfect” project that is 90% complete forever. Declare victory on Version 1.0.

Step 2: Launch and Let Go

“Launching” can mean many things.

- For Sarah, it means deploying her code to a live web server and pointing her domain name to it. The project is now public.

- For Ben, it means moving all his tools into the shed and officially starting to use it as his workspace.

This is the moment of truth. Your project is no longer a theoretical exercise; it’s a real thing in the world, doing the job it was designed to do. It can be a scary moment, but it’s the entire point of the journey.

Step 3: The Post-Mortem (The Most Important Meeting)

Whether you’re a team of one or a team of fifty, you must perform a post-mortem (or a “retrospective”). This is a structured reflection on the entire project. Do this a week or two after launch, once the dust has settled. Ask three simple questions:

- What went well? What parts of our process worked? What should we definitely do again on the next project?

- Sarah: “My tight MVP scoping was a lifesaver. Using a Kanban board kept me motivated.”

- Ben: “The pre-mortem saved me. I bought a tarp, and it did rain for three days straight. My lumber was fine.”

- What went wrong? Where did we face the most friction? What mistakes did we make? Be honest and blameless. The goal is to improve the process, not to assign blame.

- Sarah: “I wildly underestimated the time it would take to integrate the database. I should have scheduled more time for backend tasks.”

- Ben: “I bought the cheapest screws to save money, and half of them stripped. It was a false economy; I wasted hours and had to buy better ones anyway.”

- What will we do differently next time? Turn the lessons from the first two questions into concrete action items for your next project.

- Sarah: “Next time, I will double all my time estimates for backend tasks and research libraries more thoroughly before committing.”

- Ben: “Next time, I will always invest in high-quality fasteners and materials, even if the upfront cost is higher.”

This post-mortem is arguably the most valuable output of your entire project. The shed is great, the blog is great, but the knowledge of how to build better next time is priceless.

Step 4: Celebrate the Victory

You did it. You took a spark of an idea and wrestled it through fog, chaos, and frustration into a tangible reality. This is a huge accomplishment.

Do not just move on to the next thing. Take a moment to consciously celebrate. Buy yourself a gift. Take a day off. Write a blog post about your journey (meta!). Move your project’s main card to a final, glorious “Shipped” or “Completed” column.

This celebration is not frivolous. It closes the loop on the project’s emotional journey and provides the positive reinforcement you need to have the courage to start the next one.

Conclusion: The Builder’s Mindset

The framework we’ve walked through—Genesis, Blueprint, Forge, Crucible, Summit—is not a magic formula. It is a discipline. It’s a structured way of thinking that channels creative energy into productive output. It provides a scaffold to build upon, a light to guide you through the messy middle, and a process for learning from your successes and failures.

Every great creator, from a carpenter to a coder to a CEO, uses some version of this process. They define their “why,” they plan their work, they execute with discipline, they refine with ruthless honesty, and they learn from the experience.

The world is full of brilliant ideas. What the world needs are more builders—people with the grit, the process, and the courage to see them through.

So, look at your own list of languishing projects and brilliant ideas. Pick one. Start with Phase 1. Ask “Why?” Define its smallest possible core. Then, draw the map. Take the first small step. And begin the journey.

What will you build?