What is a Building Project?: Look at the skyline of any city, and you’ll see them: cranes silhouetted against the dawn, the skeletal frames of new structures reaching for the clouds. Walk through any neighborhood, and you’ll hear them: the buzz of a saw, the rhythmic thud of a hammer, the beep of a reversing truck. These are the sights and sounds of progress, of creation, of something new being brought into the world. They are the outward signs of a building project.

But what is a building project, really?

The simple answer—”the process of constructing a building”—is woefully incomplete. It’s like describing a symphony as “a collection of sounds” or a novel as “a bunch of words.” It misses the incredible complexity, the human drama, and the intricate dance of disciplines that must occur to transform a mere idea into a physical, habitable space.

A building project is a temporary, highly-structured organization of people, capital, and resources, created to achieve a singular, complex goal: the design, construction, and delivery of a physical facility. It is a monumental exercise in collaboration and problem-solving. It’s an ecosystem where visionaries, artists, scientists, financiers, and craftspeople converge. It is, in essence, a monument to managed chaos.

This guide is a deep dive into that managed chaos. Over the next 5,000 words, we will dissect the anatomy of a building project. We will go far beyond bricks and mortar to explore the core pillars that support every project, walk through its entire lifecycle from dream to reality, meet the cast of characters essential to its success, and uncover the unseen forces that can make or break it.

Whether you’re a homeowner planning a kitchen remodel, a business owner considering a new facility, a student aspiring to a career in the field, or simply curious about how our built environment comes to be, this is your in-depth explanation.

Part 1: The Anatomy of a Building Project – The Five Core Pillars

Before a single shovel hits the dirt, every successful building project must be built on a foundation of five essential pillars. Neglecting any one of them is a recipe for disaster.

Pillar 1: The Vision (The “Why” and the “What”)

Every project begins not with a blueprint, but with a need or a desire. This is the Vision. It is the answer to the two most fundamental questions: Why are we doing this? and What are we trying to create?

- The “Why” is the Purpose. It’s the core driver. A family needs more space for their growing children. A company needs a larger headquarters to accommodate its expansion. A city needs a new library to serve its community. A developer sees an opportunity to create desirable housing. This purpose is the project’s North Star, guiding all subsequent decisions.

- The “What” is the Program. The “program” is the architectural term for a detailed list of what the building needs to do and contain. It translates the vague “why” into a concrete list of requirements.

- For a house extension: The program might be: “a 500-square-foot addition containing one master bedroom with a walk-in closet, one full bathroom with a double vanity and a walk-in shower, and large windows facing the backyard.”

- For a new office: The program could be: “a 20,000-square-foot, two-story building with an open-plan workspace for 100 employees, five private offices, two large conference rooms, a kitchen/break area, and ADA-compliant restrooms on each floor.”

The Vision phase is about transforming a fuzzy dream into a defined, functional brief. It is the source code for the entire project.

Pillar 2: The Land (The “Where”)

A building is inseparable from its location. The Land is the physical canvas upon which the vision will be painted, and it comes with its own set of rules, constraints, and opportunities. Key considerations include:

- Zoning and Regulations: Is the land zoned for the intended use (residential, commercial, industrial)? Are there height restrictions, setback requirements (how far the building must be from the property lines), or historical preservation ordinances?

- Topography and Geotechnical Conditions: Is the site flat or sloped? Is the soil stable clay, loose sand, or solid rock? A geotechnical survey is often required to understand what’s happening beneath the surface, which will dictate the foundation design.

- Utilities and Infrastructure: Is there access to water, sewer, electricity, gas, and internet? Bringing utilities to a remote site can be an enormously expensive part of a project.

- Environmental Factors: Are there wetlands, endangered species, or potential for flooding? Environmental impact assessments may be required.

- Context: What are the neighboring buildings like? Is it a busy urban street or a quiet suburban cul-de-sac? A good design responds to its surroundings.

The Land is not a passive element; it actively shapes the project’s design, cost, and timeline.

Pillar 3: The People (The “Who”)

A building project is fundamentally a human endeavor. It is a temporary alliance of diverse specialists, each with a critical role to play. While we will explore these roles in more detail later, the core triumvirate at the heart of most projects is:

- The Owner (or Client): The person or entity who commissions the project, provides the vision, and pays the bills.

- The Designer (or Architect/Engineer): The person or firm responsible for translating the owner’s vision into a set of buildable plans and specifications.

- The Builder (or General Contractor): The person or company responsible for managing the physical construction, including labor, materials, and equipment.

The relationships between these three parties—often referred to as the “three-legged stool”—are paramount. Trust, communication, and a shared understanding of the goals are essential for the project’s stability.

Pillar 4: The Capital (The “How Much”)

Buildings are expensive. Capital is the financial engine that powers the entire process, from the first design sketch to the final coat of paint. This pillar involves much more than just the construction cost. A comprehensive project budget includes:

- Soft Costs: These are the intangible costs not directly related to labor and materials. They include architectural and engineering fees, permit fees, legal costs, financing costs, insurance, and taxes. They can easily amount to 20-30% of the hard costs.

- Hard Costs: This is the “bricks and mortar” cost—the price of all materials, labor, and equipment needed to build the structure.

- Land Costs: The cost of acquiring the property itself.

- Contingency: This is a crucial line item. A contingency fund (typically 5-15% of the construction cost) is money set aside to cover unforeseen problems, changes, and risks. A project without a contingency is a project planning to fail.

Securing financing—whether from personal savings, a bank loan, or investors—is a major milestone that often determines if a project can even proceed from the vision stage.

Pillar 5: The Rules (The “How To”)

You can’t just build whatever you want, wherever you want. A building project is governed by a dense web of laws, codes, and standards designed to ensure public safety, health, and welfare. These Rules are non-negotiable. They include:

- Building Codes: These are sets of technical standards for the design and construction of buildings (e.g., the International Building Code or IBC). They dictate everything from the required strength of structural beams to the number of electrical outlets in a room and the fire-resistance rating of walls.

- Permitting: Before construction can begin, the design plans must be submitted to the local Authority Having Jurisdiction (AHJ)—typically the city or county building department. The AHJ reviews the plans for code compliance and, if approved, issues a building permit.

- Inspections: Throughout the construction process, a building inspector from the AHJ will visit the site at critical milestones (e.g., after the foundation is poured, after the framing is up, after the electrical is roughed in) to verify that the work is being done according to the approved plans and codes. Work cannot proceed past these points without a passed inspection.

These five pillars—Vision, Land, People, Capital, and Rules—form the essential DNA of any building project. With this foundation in place, the journey can begin.

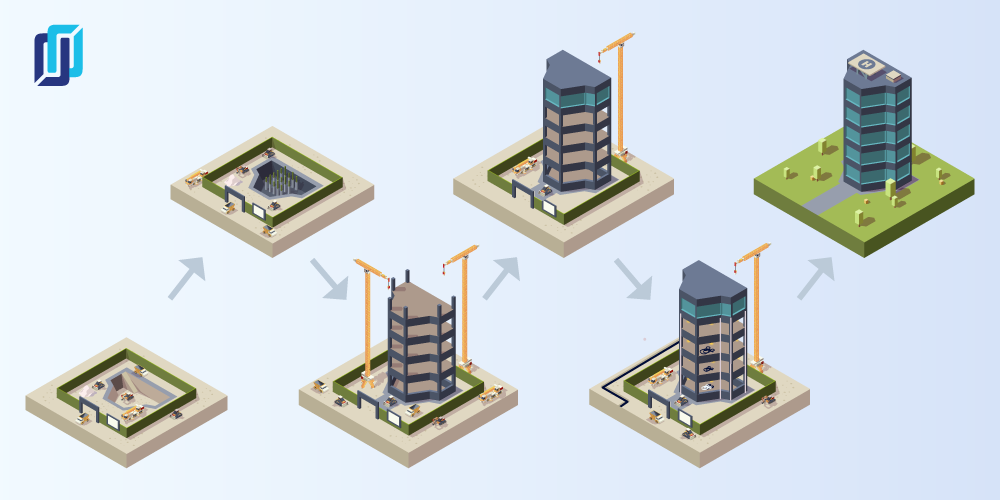

Part 2: The Project Lifecycle – A Journey in Five Acts

A building project unfolds in a logical sequence of phases. While there can be overlap, understanding this lifecycle is key to understanding the process. We can think of it as a five-act play.

Act 1: Pre-Design / Feasibility (The Dream)

This is the “should we even do this?” stage. It’s an exploratory phase where the owner, often with the help of a consultant or architect, tests the viability of the project. The goal is to make an informed ” go/no-go ” decision before investing significant capital.

- Activities: Defining the initial program (Pillar 1), site selection and analysis (Pillar 2), creating a rough order-of-magnitude budget (Pillar 4), and identifying major regulatory hurdles (Pillar 5).

- Key Question: Based on our initial understanding of the goals, the site, the likely costs, and the rules, is this project feasible?

- Outcome: A feasibility study or report that gives the owner the confidence to either proceed to the next stage or shelve the project.

Act 2: Design (The Blueprint)

If Act 1 is the dream, Act 2 is where that dream is given form and substance. This is the architect’s and engineer’s time to shine. The design phase itself is typically broken down into three distinct sub-phases:

- Schematic Design (SD): This is the “big picture” stage. The architect creates broad-stroke drawings, sketches, and simple models to explore the general layout, form, and scale of the building. It’s about establishing the basic concept and overall design direction. The owner is heavily involved, providing feedback to ensure the scheme aligns with their vision.

- Design Development (DD): Here, the approved schematic design is fleshed out with detail. The design team makes firm decisions on materials (brick or wood siding?), window types, and major building systems (What kind of HVAC system? Where will the main electrical panel go?). The structural engineer designs the skeleton of the building. Drawings become more specific and technical. The budget is refined to reflect these detailed choices.

- Construction Documents (CDs): This is the final and most intensive design phase. The design team produces a highly detailed and technically precise set of drawings and specifications. These are not just pictures; they are the legal instructions for the builder. The CD set includes everything the contractor needs to know to build the project exactly as intended, from the exact size of a steel beam to the specific model number of a faucet. This set of documents will be used for permitting, bidding, and construction.

Act 3: Bidding and Procurement (The Team-Up)

With a complete set of Construction Documents in hand, the owner needs to select a builder. This is the procurement phase. There are several ways to do this, but a common method is competitive bidding:

- Tendering: The owner, often through the architect, sends out the CD set to several pre-qualified General Contractors (GCs) and invites them to submit a bid (a price to build the project).

- Bidding: The GCs analyze the documents in detail. They send the plans to their network of subcontractors (plumbers, electricians, painters, etc.) to get quotes for their specific portions of the work. The GC then compiles all these costs, adds their own overhead and profit, and submits a final bid to the owner.

- Selection and Contract: The owner reviews the bids. While the lowest price is often a major factor, they also consider the contractor’s reputation, experience, and proposed schedule. Once a contractor is selected, a formal construction contract is negotiated and signed. This legally binding document outlines the scope of work, price, schedule, and responsibilities of both parties.

Act 4: Construction (The Main Event)

This is the phase everyone visualizes when they think of a building project. It’s when the plans on paper are transformed into a physical reality. It is orchestrated by the General Contractor, who manages a complex ballet of activities on site:

- Site Preparation: Clearing the land, excavation, and grading.

- Foundation: Pouring the concrete footings and slab that will support the entire structure.

- Framing: Erecting the building’s skeleton (wood or steel).

- Rough-Ins: Installing the guts of the building inside the walls before they are closed up. This includes plumbing pipes, electrical wiring, and HVAC ductwork (this is often called MEP: Mechanical, Electrical, and Plumbing).

- Enclosure and Finishes: Putting on the “skin” (siding, roofing, windows) and then moving inside to install drywall, flooring, paint, cabinetry, fixtures, and all the final touches that make a building habitable.

Throughout this process, the GC is responsible for scheduling the work of dozens of subcontractors, ensuring site safety, managing the budget, and coordinating with the city inspectors at each required milestone. The architect also plays a role, visiting the site periodically to ensure the work is conforming to the design intent (this is called “Construction Administration”).

Act 5: Post-Construction and Occupancy (The Finish Line)

The construction work is done, but the project isn’t over. This final act is about formally closing out the project and handing it over to the owner.

- Substantial Completion & Punch List: When the building is essentially ready for use, the architect inspects it and creates a “punch list”—a list of minor defects or incomplete items that need to be fixed (e.g., a scratch on a wall, a faulty light switch).

- Final Inspections & Certificate of Occupancy (CO): The final city inspections are completed. Once the AHJ is satisfied that the building is fully code-compliant and safe, they issue a Certificate of Occupancy. It is illegal to occupy a new building without a CO.

- Handover and Commissioning: The contractor formally hands the keys over to the owner. They provide documentation and training on how to operate the building’s systems (like the HVAC and fire alarm). This process, known as commissioning, ensures everything works as designed.

- Project Closeout: Final payments are made, all contracts are closed, and the warranty period (typically one year) begins, during which the contractor is responsible for fixing any defects in materials or workmanship.

Only after this final act is the building project truly complete.

Part 3: The Cast of Characters – Who Builds a Building?

As we’ve seen, a project requires a diverse team. Let’s look more closely at the primary roles and their responsibilities.

The Owner / Client / Developer

The owner is the project’s initiator and ultimate authority. They provide the vision, make the key decisions, and bear the financial risk. Their primary responsibility is to be clear about their goals and to make timely decisions so the project doesn’t stall. Owners can be individuals (a homeowner), a private company, or a public entity (a school district or government agency).

The Design Team

This team is responsible for the “what” and “how” of the building’s design.

- The Architect: The lead designer and the owner’s primary advocate. The architect synthesizes the owner’s vision, the site’s constraints, and the building codes into a coherent and functional design. They are the master planner, coordinating the work of all other design consultants.

- The Engineers: These are the technical specialists who make the architect’s design work and ensure it’s safe.

- Structural Engineer: Designs the building’s “bones”—the foundation, beams, and columns—to ensure it can withstand gravity, wind, and seismic forces.

- MEP Engineer (Mechanical, Electrical, Plumbing): Designs the building’s “organs” and “circulatory system”—the heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); the power and lighting systems; and the water supply and drainage systems.

- Civil Engineer: Designs the project’s connection to the outside world—site drainage, roadways, parking lots, and utility connections.

The Construction Team

This team is responsible for the physical execution of the design.

- The General Contractor (GC): The “conductor” of the construction orchestra. The GC holds the prime contract with the owner and is responsible for delivering the finished project for the agreed-upon price and schedule. They hire and manage all the subcontractors, procure materials, and ensure the safety and quality of the work on site.

- The Subcontractors: These are the specialist trade contractors who perform the bulk of the hands-on work. There are subcontractors for every conceivable task: excavation, concrete, framing, roofing, plumbing, electrical, drywall, painting, and so on. They are hired by and report to the GC.

- The Project Manager (PM): Often an employee of the GC, the PM is the day-to-day manager of the project, handling the schedule, budget, and communication between the field, the office, and the design team.

The Authorities Having Jurisdiction (AHJ)

This is the official body, usually a municipal department, responsible for enforcing building codes and regulations. They are the impartial referees whose job is to protect the public. Their key players are the Plan Checker, who reviews the documents for a permit, and the Building Inspector, who visits the site to ensure the construction matches the approved plans.

Part 4: The Unseen Forces – Risk, Change, and Communication

Finally, to truly understand a building project, we must look beyond the tangible processes and people to the invisible forces that shape its journey.

Risk Management

Every project is fraught with risk. The ground may not be what the geotechnical report suggested. A key material may suddenly become unavailable or skyrocket in price. A week of torrential rain can halt all progress. A key subcontractor might go out of business.

Successful project management is not about avoiding risk—that’s impossible. It’s about identifying, assessing, and mitigating risk. This is the primary purpose of the contingency fund. It’s also why experienced teams conduct “pre-mortems,” where they imagine the project has failed and work backward to identify all the potential causes, allowing them to create proactive mitigation strategies.

Change Management

No plan is perfect. The phrase “no plan survives contact with the enemy” is doubly true in construction, where the “enemy” can be anything from an undiscovered utility line to the owner changing their mind.

Changes during construction are formalized through a document called a Change Order. A change order is a mini-contract that describes the change in the scope of work and its impact on the project’s cost and schedule. For example, if the owner decides they want granite countertops instead of the laminate specified in the original plans, the GC will issue a change order for the owner to sign, detailing the additional cost and any potential delay. Managing change effectively is critical to keeping a project from spiraling out of control.

Communication

If capital is the engine of a project, communication is its lifeblood. A breakdown in communication between the owner, architect, and contractor is the single most common cause of project failure.

Good communication is structured and documented. It involves:

- Regular Meetings: Weekly site meetings with the key players to review progress, address problems, and plan upcoming work.

- Formal Documentation: Using standardized documents like Requests for Information (RFIs) (a contractor’s formal question to the architect) and Submittals (the contractor providing product data to the architect for approval) creates a clear paper trail.

- A Collaborative Mindset: The most successful projects are those where the parties see themselves as partners in a shared enterprise, not as adversaries in a zero-sum game. When problems arise (and they will), a collaborative team works together to find the best solution for the project, rather than trying to assign blame.

Conclusion: A Symphony of Creation

So, what is a building project?

It is the tangible result of a vision, tethered to a piece of land, funded by capital, guided by rules, and brought to life by a dedicated team of people. It is a journey through a structured lifecycle of dreaming, designing, planning, building, and finishing.

It is far more than just bricks and mortar. It is a complex, dynamic, and challenging endeavor that demands a delicate balance of art and science, creativity and pragmatism, collaboration and command. It is a temporary alliance forged in the pursuit of a permanent goal. When you next see a crane on the horizon or hear the sound of a hammer down the street, you’ll know that you’re witnessing not just the construction of a building, but the performance of a modern symphony of creation.